Me: What’s 7999999999 plus 1?

My son: That’s too big Daddy, I can’t add those!!

Me: Okay, let’s try a simpler problem. What’s 9 + 1?

Son: 10

Me: 99 + 1?

Son: 100

Me: 999 + 1?

Son: 1000

Me: 9999 + 1?

Son: I don’t know how to say the next number. Oh wait! TEN thousand (proudly).

Me: 99,999 + 1?

Son: 100, 000

Me: 999,999 + 1?

Son: How do you say 1000 thousands?

Me: 1 million

Son (laughs): Okay the last one is 1 million then.

Me (continuing): What’s 9,999,999 plus one?

Son: 10 million.

Me: What’s 99,999,999 + 1?

Son: 100 hundred million.

Me: 999,999,999 plus one?

Son: How do you say 1000 millions?

Me: One billion.

Son: That’s the answer then, 1 billion.

Me: Okay, now try the first problem. What’s 7,999,999,999 plus one?

Son (no hesitation): 8 billion.

Son: What’s 1000 billion?

Me: One trillion.

Son: What’s 1000 trillions?

Me: One quadrillion.

Son (giggles): And then?

Me: Quintillion

Son: What’s next!

Me: Sextillions, then Septillions, then Octillions, then Nonatillions, then probably Decitillions.

Son: What’s next?

Me: Probably Endekatillions and Dodekatillions, but that’s the limit of my Greek.

Me: What if we played our adding game forever?

Son: Infinity! But we’d have to play in Heaven because even if we played until the end of our lives, we still wouldn’t reach infinity.

(Leads to a long discussion on whether heaven exists and where we go when we die.)

Generalizing

My son was given the following problem in his math club.

We can see that 2 + 2 = 4 and 2 × 2 = 4 and similarly 1 + 2 + 3 = 6 and 1 × 2 × 3 = 6.

Can you find four whole numbers where their sum and their products are the same? What about five whole numbers?

Spoiler alert: If you read further, you will get the solution to this problem. You may want to try it out yourself first. Scroll down when you are ready.

My son found 1 + 1 + 2 + 4 = 8, 1 × 1 × 2 × 4 = 8 and 1 + 1 + 1 + 2 + 5 = 10, 1 × 1 × 1 × 2 × 5 = 10. From this he conjectured that if you take a bunch of 1s followed by 2 and then followed by the sum of the 1s and the 2, that this list of numbers has the property that it multiplies and adds to give twice the last number in the list.

I asked him if he could prove that his conjecture is always true. He said, “The number of numbers minus two is the number of ones we need. Then plus two, that’s now the same value as the number of numbers at the end. If you add all of those numbers, you’ll get twice the number. And if you multiply all of those numbers you get 2 times the number, same value as the sum, because none of the 1s changes the value.”

“Or,” he continued, “If the number of numbers is n, then the number of 1s is n – 2, followed by a 2, followed by n. n – 2 + 2 is n. So the sum is 2n. The product is 1 times 1 times … and so on times 1 and then times 2 and times n which is also 2n.”

Which is greater?

This is the equivalent problem in a different representation.

My son was comparing two fractions to decide which is bigger (a problem that appears in his Beast Academy workbook).

He looked at the fractions and noticed that if he changed the first fraction, he could get the denominators to be closer together.

Him: “Oh, now I know that is larger than

!”

Me: “How do you know that?”

Him: “If we had we would know that is more than

since

is more than

. We just have 1 more

so for sure

is more than

.”

What I find interesting about this is that I was taught that in order to compare two fractions, one first needs to be able to find a common denominator. Obviously that’s not true.

Inductive reasoning

Tonight I introduced the sad tale of Daedalus and Icarus to my son. In case you are not familiar with the story, Daedalus and Icarus are stuck in the tower in the middle of the maze with a horrible minotaur blocking their escape. Daedalus builds wings and they try and fly away.

In the mathematical version of this story, created by Gordon Hamilton, Daedalus “flies” by choosing a number. If the number is odd, he multiplies it by 3 and then subtracts 1. If it is even, he divides it by 2. For Icarus if the number is odd, he multiplies it by 3 and adds 1. If it is even, he also divides it by 2. The objective is to pick a number that does not eventually end up as a 1 because this means that Daedalus or Icarus just crashed into the ground.

My son and I played this game (based on the Collatz Conjecture) and quickly found a value of Daedalus that allows him to fly away and escape the maze. We then started trying to find values that allow Icarus to escape (we haven’t succeeded yet).

At one point my noted the following:

You know, Dad. There are an infinite number of solutions to the Daedalus problem. If you have a solution, to find another starting number that works, just double it, and so on. We can keep finding new solutions by doubling whatever number we have. Since we have one answer that works, we know there are an infinite number of ones that do.

This is essentially inductive reasoning. He’s reasoned that if we know case n works, we can find a larger case by doubling it. Since we know at least one solution for Daedalus works, and that we can double as many times as we like, then we must have an infinite number of solutions.

Three plus four is seven

While driving on the highway, my wife had the following exchange with my three year old son, Timon.

“Mom, what’s three plus three?”

“Six.”

“Mom, what’s four plus four?”

“Eight.”

“So… three plus four is seven.”

My wife was so stunned, she told me later, she almost stopped the car to tell me.

Timon asking us questions about addition is nothing new. He’s been trying to participate in a similar game my older son plays with me. What’s remarkable here is that Timon has derived the addition fact for three plus four.

Timon also recently noticed that one plus three and two plus two both equal four and showed me on his fingers why he knew it was true. He’s playing with addition of small numbers, sometimes asking me what the sum is, sometimes showing me by counting out on his fingers. He has yet to count on from a number he knows (he starts counting at one each time) but he does recognize groups of objects up to four and sometimes five in size without counting directly.

My point here is to pay attention when your children discover ideas on their own. They might just surprise you.

Deciphering Roman Numerals

My son was reading one of his novels recently which had Roman Numerals as the chapter titles. He’d learned about Roman numerals in kindergarten but had forgotten what L meant. Here’s how he figured it out again.

I must be 1 because it was the first chapter.

I forgot what L meant and when I looked at the last chapter, which was LII, I thought L was 100. Then I looked at the page number, which was 504, and decided that was impossible because that would mean each chapter would be only five pages long which made no sense. So I decided L must mean fifty.

Knowing a little bit about Roman numerals was probably helpful here, but so was knowing something about how books work and what kind of answer would be realistic. When children don’t know what kind of answer is reasonable, it makes doing the mathematics harder.

Conservation of Cream Cheese Theorem

“I want a knife. Can you give me a knife?”, Timon asked.

“Why do you want a knife?” I responded.

“I want to spread my cream cheese. On my cracker.”

“Why do you want to spread your cream cheese?”

“Because I want more cream cheese,” replied Timon.

I gave Timon a knife and he proceeded to take the cream cheese that was on his cracker and spread it out until it covered much more of his cracker. Then he smiled and ate the cracker.

Timon doesn’t yet know that no matter how he manipulates his cream cheese, there’s always going to be the same amount. He has yet to learn the Conservation of Cream Cheese Theorem.

But he from his actions we can infer what he does understand that the more area of cream cheese there is on his cracker, the more cream cheese there is. This is true, provided the thickness of the cream cheese is constant.

I wonder how much longer he’ll think that he can get more of something by spreading it out.

We have four people in our family

“We have two people.”

Timon, who is 3 years old, holds up 2 fingers on the same hand.

“What if Mommy comes back? Then we have three people. See? Three people.”

Timon holds up 3 fingers on the same hand and then says, “And if Thanasis comes too? Then we have four people. Four people.”

Timon holds up four fingers on one hand for emphasis. Then he giggles and holds up two fingers on one hand and two fingers on the other hand and says “See four people?”

I ask, “And what if Grandpa comes? How many people then?”

Timon says quickly, without any obvious counting with his fingers, “Five!” and then holds up all five fingers on one hand. Here, I notice him counting on rather than counting from one.

“What if Grandma comes too?”, I ask.

Timon, without speaking runs up and shows me five fingers on one hand and one finger on his other hand and then says, “Six people.”

And then he’s done with this game and moves on.

Later I ask him again how many people are in our family and he holds up five fingers, looks at them and says, “I need to take one away. Four people” and folds his thumb up next to his hand.

This is the use of three different representations of numbers from 1 through 6, specifically the oral naming of the numbers, the use of his fingers to show the numbers, and then actual number of people being represented, and Timon is moving between the three representations fluently.

But he’s also only doing this for the first six numbers and I know that he doesn’t know the symbols for these six numbers yet. I’m also not sure yet that in every instance of these numbers appearing around him that he’s as fluent as when he is counting people. And as I recall with my older son, he was fluent with counting people before he was able to count other things.

I especially noticed this interaction because this is the first time I have seen him move between number representations greater than 4 things so effortlessly.

Noticing number strategies

Recently I ran a math class for a few younger students, including my son. The objective of this class were to start making connections between how students visualize numbers and early arithmetic strategies.

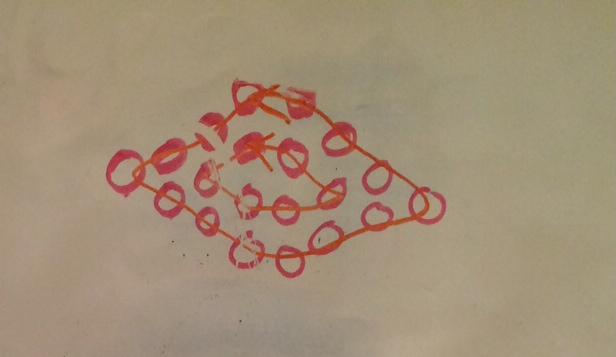

Here are some of the various ways students visualized a group of dots to figure out how many total dots there were.

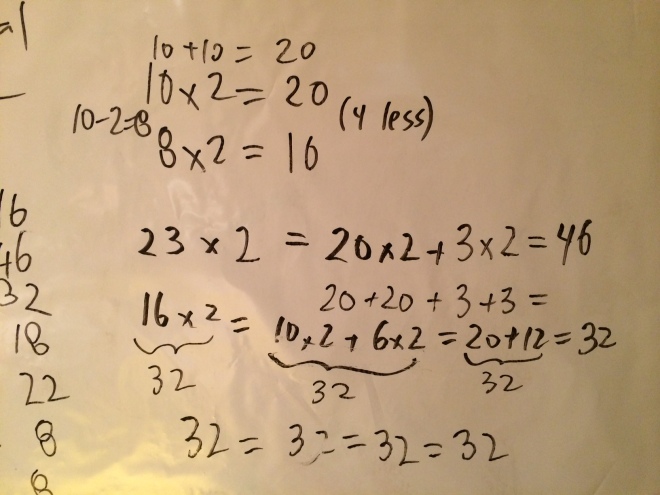

Here are some of the strategies students used when they doubled numbers in their pattern.

I asked students to look at the visualizations for the dot patterns and the arithmetic patterns and see if they noticed anything in common between the dot visualizations and the doubling strategies. They didn’t.

So I told them to find a partner, talk to their partner about the same questions, and then told them we would discuss it again. Two minutes later, I asked students to sit back down in the group after their discussions and re-asked the same question: “What is common to the strategies you (as a group) used for the dot visualizations and the doubling strategies? What is the same about what you did?”

One student said that in both cases, the students counted in order to find the answer, which was true. In both the dot visualizations and the doubling strategies, one strategy at least some students used was counting.

Another student said that in the dot pattern and the doubling strategies, we were trying to duplicate something. Not everyone knew what he meant by duplicating, so he explained it again, and I revoiced him and used the word doubling, which everyone understood.

Finally, another student had an epiphany. “When we did the dot pattern and when we did the doubling, something in common is that we figured out a big group and left some over to figure out at the end.”

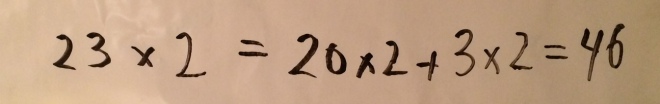

Here are the actual two strategies he linked together with his observation:

In the first one, in order to figure out 23 x 2, first we do 20 x 2 and we save the 3 to figure out later. In the second one, first we counted the perimeter and saved the inside shapes for later.

I’m excited by this observation as I had never thought of thinking of the distributive property as “saving part of the calculation” for later (although I have often seen other visualizations of the distributive properties).

Thinking about rates and times

As we were traveling back from track practice tonight, my son and I had a fairly natural conversation about driving on the highway.

Son: “How fast are we going right now, Daddy?”

Me: “According to my speedometer, we are going 2 miles over the speed limit. Oops!”

Son: “So if we were traveling for a whole hour, we would only go 2 miles??” Here my son is double-checking his reasoning with me and thinks I might be a bit crazy to suggest that we are going only 2 miles an hour. He has a strong sense that the speed he can observe outside the car does not match the calculation he has done.

Me: “No, I mean we are traveling 52 miles an hour and the speed limit is 50 miles an hour, so we are going 2 miles an hour too fast right now.”

Son: “Oh. Okay.”

Me: “I have a question for you. If we were traveling at 60 miles an hour, how far would we get in ten minutes?” Now, if we were not in a car and I was not trying to strike up a conversation with my son, I probably would not have asked this question. In the context of driving a car down a highway, I think this makes sense as a conversation starter – at least to a parent who is a mathematician and a mathematics teacher.

Son: “10.” (nearly instantly)

Me: “How do you know that?”

Son: “Well, there are 60 minutes in an hour and we are traveling at 60 miles an hour, so ten minutes must be ten miles. I don’t know how to explain this, Daddy!” Actually, you did explain it just fine son, but somehow you feel your explanation is inadequate.

Me: “I think I understand. The miles and the minutes have to be the same.” My son did not articulate his thinking in this way. I don’t know if this was helpful or not, but I felt that he wanted me to revoice what he had said using different language.

Son: “Yeah.”

Me: “I have a harder question.”

Son: “Okay, but I want it to be just slightly harder not a lot harder, okay?”

Me: “Okay. If we were traveling at 50 miles an hour, how far would we travel in ten minutes?” This question comes straight from a video I watched of Magdalene Lampert teaching during a workshop she ran over the summer. I was curious, how might my son approach this problem?

Son: “Hrmm. Maybe 9 miles an hour?” I love that my son’s first instinct is to estimate.

Me: “How do you know that?” I always ask this question, so this is normal for my son, rather than being like a quiz. I’m not quizzing him to find out how he understands, I am genuinely curious.

Son: “Well, it has to be less than 10 miles an hour. 50 is less than 60 and 9 is less than 10.”

Me: “How could we double-check that?” This is the teacher in me. I’m never satisfied with the first explanation.

Son: “We need to find nine times six. Hrmm. Nine plus nine plus nine plus nine plus nine plus nine.” My son was probably counting these nines in his head but he would have had to keep track of how many nines he was counting a couple of years ago.

Me: “What is that?”

Son: “Nine plus nine. Eighteen. And nine. Uh… I don’t know.”

Me: “Can you work it out? Also, I recommend paying attention to the answer.” This comes from MP7 in the Common Core and George Polya’s heuristics for problem solving — pay attention to the form and structure of your answer to problems as it can make other problems easier.

Son: “Okay. 27. Oooooohhh. Plus 9. 36. Plus 9. 45. I see the pattern. Plus 9. 54. Plus 9. Oh I can stop.” Meanwhile, while my son added on the nines, for each addition I pointed out the associated multiplication fact.

Me: “So does nine work?”

Son: “No, it’s too big. Let’s try six.”

Me: “Okay. Go ahead.”

Son: “6 and 6 is 12. 12 plus 6 is eighteen. Eighteen plus six is 22. No, 24. 24 plus 6 is 30. 30 plus 6. No, it doesn’t work. It’s too small.” I continue repeating the associated multiplication facts for each multiple.

Me: “What’s next?”

Son: “Let’s try 7. No, that will probably be too small. Let’s try 8. 8 plus 8 is 16. 16 plus 8 is 24.” At this point, I said that 8 times 3 is 24. My son stopped adding, “Really? Hunh.”

Me: “Yes.”

Son: “24 plus 8 is 32. 32 plus 8 is 40. 40 plus 8 is 50, no 49, no 48! Too small. It must be between 8 and 9.” Do kids that understand numbers only as counting objects recognize that there are other types of numbers in between the ones we use for counting? It seems to me that kids need plenty of experience with situations that require other types of numbers to motivate an intellectual need for those types of numbers. We don’t go look for tools, even thinking tools, arbitrarily; without some clear kind of need for the tool.

Me: “Okay.”

Son: “Hrmm. Maybe it’s 8 and a half. No, that’s too big because 6 halves is 3.”

Me: “Right, and then we would have 48 and 3 which is 51. Too big.”

Son: “It can’t be 8 and a quarter either. That would be 49 and a half.”

Me: “So it must be between 8 and a quarter and 8 and a half.” This is a key idea that I am sorry I did not let my son develop himself.

Son: “What about 8 and a third? Let’s see. YES!! 6 thirds is two, so it works! I got it! Daddy, that problem was not a ‘little bit harder’ than the other problem. It was WAY harder.”

I find it hard not to turn off my teacher self when my son and I are discussing mathematics. I find myself really curious about how he will approach problems and I often find myself straddling the line between pushing him to articulate his thinking and just being a bit annoying.

On the other hand… the teacher part of me is now curious; which mathematical standards and practices did my son and I uncover in our conversation together? I remember Magdalene Lampert telling me once that when she teaches, she tries to hold all of the standards for the year in her head while working with students because she is never really working on one specific thing at once; she is trying to connect all of the ideas of the year together.